Have analytics gone too far? Author argues we're devaluing human creativity

As a magazine storyteller, Chris Jones has written about astronauts, filmmakers, game show winners, magicians, one U.S. presidential nominee, the youngest manager in pro baseball, and Conor McGregor, who put Jones in a rear chokehold at his request. (Certain he could stay conscious, Jones passed out in seconds.)

Jones never profiled Billy Beane, though he tried. When Beane was general manager of the Oakland Athletics, Jones asked to shadow him to learn about his approach to roster-building. Sure, Beane said – just not yet. Another writer was hanging around the A’s front office, but Beane doubted the guy would publish anything.

“And then ‘Moneyball’ comes out,” Jones said over the phone last week, referring to Michael Lewis’ 2003 book. “Then it became a huge bestseller and the movie, and changed the world.”

By spotlighting how Beane ran the A’s, Lewis made analytics popular. Crunching baseball’s voluminous data helped Beane acquire undervalued players, like batters who got on base a lot, for little cost. Everyone began to look for overlooked opportunities. Baseball teams shift a lot nowadays. The NBA ditched the mid-range jumper to shoot threes in bulk. Win probability models spur NFL coaches to go for it more often on fourth down.

Jones enjoyed “Moneyball” but thinks the movement it inspired went too far. His new book – “The Eye Test: A Case for Human Creativity in the Age of Analytics,” out Tuesday – counters the notion that numbers should drive decision-making in all walks of life, sports included. He’s met a lot of curious, adaptive, empathetic, expert people. What happens, he wonders, when the world discounts what they see and feel?

“I’m worried that people are going to write that the book is an anti-‘Moneyball’ book,” Jones said. “It’s not. I just think data has its limits. And where it has its limits, those are opportunities for people to shine.”

Jones, who’s written for Esquire, The New York Times Magazine, ESPN, Grantland, and Netflix, lives near Toronto in Port Hope, Ontario. He spoke to theScore about a range of topics that relate to his book, including Derek Jeter’s defense, the Tampa Bay Rays’ 2020 World Series loss, and the ingenuity of Jason Witten and Mohamed Salah.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

theScore: “The Eye Test” covers a lot of ground: sports, policing, Hollywood, the 9/11 victims compensation fund. Everywhere in life, you argue, problem-solving could stand to be more humane and less reliant on algorithms and spreadsheets. What made you want to mount that argument?

Jones: My first sportswriting job was as a baseball beat writer. I covered the Blue Jays for (Canadian newspaper) the National Post. I learned a ton from old baseball guys. Jim Fregosi was the manager of the Jays. Every Sunday we were on the road, he would sit in the dugout with me and teach me something about the game. I still remember one I got on the changeup in Cleveland. It was 20 minutes on this single pitch.

“Moneyball” came out a few years later. When it came out, I was like, “This is super cool.” I think the movie’s fantastic. But then I felt like that movement started going too far, and those old guys who taught me stuff in the late ’90s were exactly the kind of people who were being ridiculed or dismissed as morons, basically – do you know what I mean? – that they didn’t know what they thought they knew.

I think data does provide some useful corrections. I’m not saying I’m anti-data. I’m just saying I think that, like a lot of revolutions, it’s gone too far and the collateral damage is starting to be something that we need to reckon with. I think there are claims being made about analytics that are not true, and if you dare to raise opposition, you’re cast as a heretic or a moron or you believe in fairy dust.

What I’m trying to say is: No. There’s a place for data, but there’s also a place for experience. There’s still a place for multiple perspectives. Nearly 20 years after “Moneyball” has come out, I think a lot of people will, hopefully, agree they’re feeling a little unease about the path that we’re on.

You bring up how Tampa Bay lost the 2020 World Series because of a math decision. Blake Snell was cruising in Game 6, Kevin Cash pulled Snell before the Dodgers batted against him for a third time, and L.A. took the lead. The counterpoint is that the Rays’ analytical approach got them to the World Series in the first place. This got me wondering: Where, to you, is the line at which analytics stop being valuable?

I don’t know that there is a hard line. I would be a moron to make the case fully against analytics. It works for Tampa Bay. It worked for Oakland to get into the playoffs (under Beane). They’re valuable to a point.

But then I think what sometimes happens, human discretion gets cast aside and you always follow the math. There has to be a moment where you trust the guy or you trust your own wisdom. You trust your experience.

Why do we only choose one perspective? Why does analytics become the law? Why can’t it be analytics plus our sense of things? The analytics movement will talk about the pre-“Moneyball” time in sports as being blind, archaic. I feel like we’re trading one kind of blindness for another.

There’s a guy, Ian Graham, who’s a physicist. He’s a backroom architect at Liverpool. He refuses to watch games because he thinks it taints him – that the emotion of it will make him less objective than he needs to be. I’m like, well, you’re just choosing one myopia (over) another. You’re trading the pure eye test for pure analytics. Isn’t there room for both?

The book opens with an Albert Einstein quote: “Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.” If sports did more to encourage imagination, creativity, and discretion, what effect would that have on the product?

For me, if you get a really smart person working on something using creativity and imagination, that’s now the competitive advantage. There’s no baseball team that isn’t using analytics now. There’s a limit to what they can divine. You might find a new statistic, or you might find a better way to statistically analyze defense. But at some point, you’re all using the same figures.

The pendulum has swung in favor of analytics. Again, I’m not against them. But I do feel like it’s time for a correction, where you bring it back a little bit. That’s your competitive advantage now: It’s in finding the right person for the right role.

About people who’ve spent a lifetime in their sport, you write, “their bones can reveal its truths better than any spreadsheet.” Who’s a person you had in mind when you wrote this?

I did a story (for ESPN The Magazine in 2014) on Mike Jirschele, who was the Kansas City Royals’ third base coach. He spent, like, 36 years in the minors before he finally got to the majors. His son, Justin, is the youngest manager in professional baseball. I spent a lot of time with both of them.

When I was with Justin, I closely watched a baseball game that he was managing. After the game, we broke it down. He was telling me things that I didn’t even see. For him, these were obvious things. I was like, man, you understand this game because you’ve grown up with it. Because you’ve been around this game since you were a baby. And because after every game you’ve ever played or coached or watched, you and your dad have talked about it.

Steven Gerrard was a major player at Liverpool, and then he moved to the LA Galaxy. I got to watch a game with him. He was doing remarkably accurate analyses of players he’d never seen before. He’d be like, “I don’t know who No. 6 is, but blah, blah, blah,” and he’d be bang-on about who that guy was.

The book is not a case for random gut or flipping coins. But when you’re smart – when you’ve earned an understanding of something – those people are so valuable. You might have a super good quant on your side, but if you also have someone like Steven Gerrard on your side? That’s only an advantage.

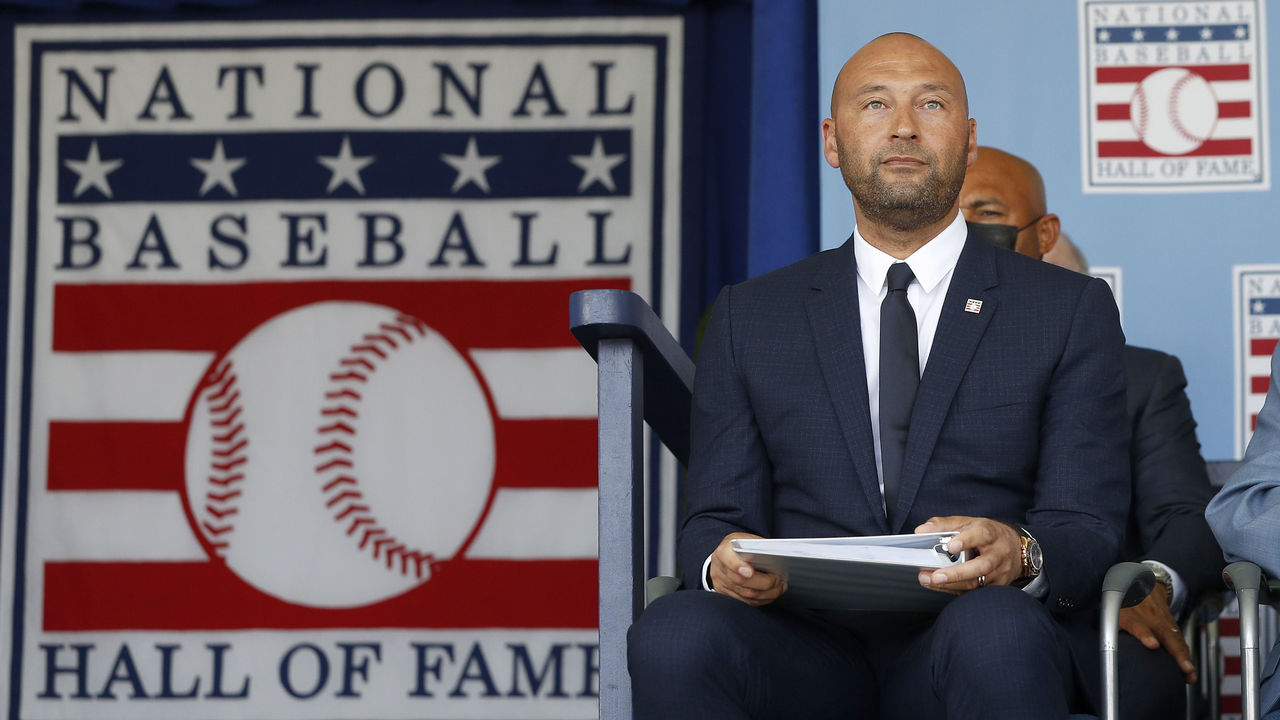

This seems to be where Derek Jeter enters the picture. He won five Gold Gloves, but the metrics show he was a poor fielding shortstop with limited range. Yet he made spectacular plays, like his famous flip in the playoffs against Oakland. To you, what does Jeter represent about the tension between analytics and creativity?

He’s always held up as the reason you can’t trust your eyes. The truth is the eye test and statistics dovetail pretty nicely when it comes to baseball defense. Ordinary fans are pretty good judges of whether someone is good at defense or not.

Jeter is this exception that’s always used as the rule. That’s a narrative sin. That’s what analytical guys always talk about with narrative: “You’re picking and choosing. You can make any argument if you’re selective enough.” That’s what they’re doing with Jeter.

If he was a below-average defender, he still made some amazing plays. He was a great shortstop despite some serious limitations. His knowledge, his wisdom, his experience, all of those things allowed him to make a play like the flip. For me, he’s an optimistic story; a guy who doesn’t have all the physical tools of another player can still rise to greatness given enough passion and attention to detail and practice and time.

He’s the embodiment of what I’m talking about. You earned the knowledge. You put the time in. And you see things that other people don’t see because you love and understand this game in a different way.

You wrote about a play that Jason Witten made to great effect throughout his NFL career. He’d run upfield on the Y Option and choose to turn left or right. What do you find so compelling about Witten and this route?

It’s everything I believe in, which is that you can take a simple, basic, seemingly binary thing and make magic out of it if you understand it better than anybody else. Jason Witten was a huge competitive advantage for the Cowboys because he could do things and saw things that other people couldn’t do or see. He could do it with the most basic route.

The Y Option, as he says, it’s not sexy. It’s left or right. How much thought could go into that? But even that gives you opportunities for greatness and difference and distinction. Imagine a much more complex thing, like policing, like medicine. If you can find a way to be great running the Y Option, imagine the possibilities in other fields of endeavor.

When you spend time around smart, interesting people, you can’t help but be inspired by the way they do what they do. Someone like Jason Witten – God, he was awesome. He was awesome at something that you wouldn’t think someone could be awesome at. But he was. There’s beauty in it.

What athlete do you like watching the most these days?

I find him completely confounding: Mo Salah for Liverpool. He had one great season (in 2018), and I wrote a piece that was like, “They need to sell him. He had one great season. It’s a fluke.” Then he did kind of have a downish year, and now he’s arguably the greatest goalscorer in the game. I watch him going, “How did you keep getting better?”

He scored (last) week against Chelsea. I’m a goalkeeper. He made this little fake, (as if) he was going across the net, and instead dumped it short-side. The goalkeeper bit on the fake. I would have bit on the fake. He does stuff that’s so subtle and beautiful. That goal is a good example. The statistics will show that he scored a goal from close range. But when you watch how he got the goal, it reveals so much more about him as a player.

It’s something that Ian Graham, the Liverpool (analyst) who’s looking at his spreadsheets, wouldn’t see. He’d appreciate him as a goalscorer, but he wouldn’t know exactly what makes him great.

It seems like a good example of how analytics and personal brilliance work in tandem. Liverpool has a data-driven approach and Mo Salah, this transcendent player who helps make them a terrific team.

Why would you ever choose to see things one way? Especially complicated things. This will sound a little weird, maybe, but I think we’re all taking in more information at the moment than humans are designed to take in. Because processing information is sometimes hard, we just sort: “I’m on that side. I’m not for that. I am for that.”

It’s making us black-and-white thinkers. For me, there’s so much beauty and possibility in the gray, in the nuance – in where these two things meet. If I had Ian Graham analyzing a football match and I had (Liverpool manager) Jurgen Klopp analyzing a football match, then I think I could really find the truth.

Outside of sports, who’s your favorite character in this book?

Teller, the magician. He gave me my favorite quote that I’ve ever gotten: “Sometimes, magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect.”

He does magic that is so confounding, other magicians are completely fooled by him. I went to his house and he gave me a deck of cards. He’s like, “I want you to pick a card out of this deck. Don’t show me.” I cupped the deck. I looked at the card. He’s like, “OK, just remember that card.” Half an hour later, we went outside. There was a sculpture of a big bear in the yard. The bear starts talking and goes, “Was your card the three of clubs?” And it was.

The answer to how that happens is time. It’s loving it more than somebody else. Putting the time in, being careful, always striving toward improvement, watching, learning. He has a voracious appetite for magic and magicians past.

For me, he’s the ideal of how you make something beautiful, which is basically what the book is for me. I hope people read the book and are inspired to do something awesome.

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.

Latest Comments